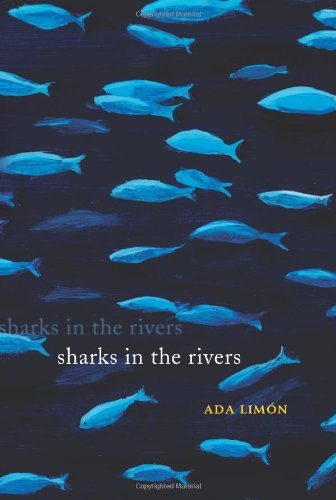

Sharks in the Rivers

We’ll say unbelievable things

to each other in the early morning—

our blue coming up from our roots,

our water rising in our extraordinary limbs.

All night I dreamt of bonfires and burn piles

and ghosts of men, and spirits

behind those birds of flame.

I cannot tell anymore when a door opens or closes,

I can only hear the frame saying, Walk through.

It is a short walkway—

into another bedroom.

Consider the handle. Consider the key.

I say to a friend, how scared I am of sharks.

How I thought I saw them in the creek

across from my street.

I once watched for them, holding a bundle

of rattlesnake grass in my hand,

shaking like a weak-leaf girl.

She sends me an article from a recent National Geographic that says,

Sharks bite fewer people each year than

New Yorkers do, according to Health Department records.

Then she sends me on my way. Into the City of Sharks.

Through another doorway, I walk to the East River saying,

Sharks are people too.

Sharks are people too.

Sharks are people too.

I write all the things I need on the bottom

of my tennis shoes. I say, Let’s walk together.

The sun behind me is like a fire.

Tiny flames in the river’s ripples.

I say something to God, but he’s not a living thing,

so I say it to the river, I say,

I want to walk through this doorway

But without all those ghosts on the edge,

I want them to stay here.

I want them to go on without me.

I want them to burn in the water.

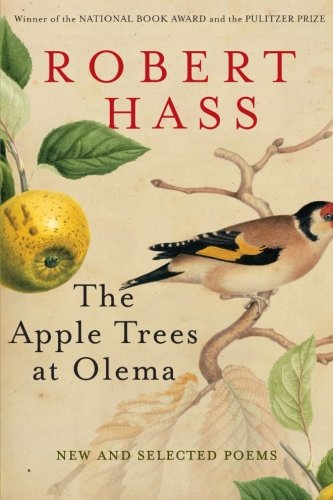

Vintage

They had agreed, walking into the delicatessen on Sixth Avenue, that their friends’ affairs were focused and saddened by massive projection;

movie screens in their childhood were immense, and someone had proposed that need was unlovable.

The delicatessen had a chicken salad with chunks of cooked chicken in a creamy basil mayonnaise a shade lighter than the Coast Range in August; it was gray outside, February.

Eating with plastic forks, walking and talking in the sleety afternoon, they passed a house where Djuna Barnes was still, reportedly, making sentences.

Bashō said: avoid adjectives of scale, you will love the world more and desire it less.

And there were other propositions to consider: childhood, VistaVision, a pair of wet, mobile lips on the screen at least eight feet long.

On the corner a blind man with one leg was selling pencils. He must have received a disability check,

but it didn’t feed his hunger for public agony, and he sat on the sidewalk slack-jawed, with a tin cup, his face and opaque eyes turned upward in a look of blind, questing pathos—

half Job, half mole.

Would the good Christ of Manhattan have restored his sight and two thirds of his left leg? Or would he have healed his heart and left him there in a mutilated body? And what would that peace feel like?

It makes you want, at this point, a quick cut, or a reaction shot. “The taxis rivered up Sixth Avenue.” “A little sunlight touched the steeple of the First Magyar Reform Church.”

In fact, the clerk in the liquor store was appalled. “No, no,” he said, “that cabernet can’t be drunk for another five years.”